Many of the accidents and deaths that occur on European roads are caused by drivers whose performance is impaired by a psychoactive substance. Alcohol alone is estimated to account for up to 10 000 road deaths a year in the EU, one quarter of all road deaths (1). But, says the EMCDDA, no comparable figures are available for road accidents relating to illcit drugs and psychoactive medicines. This means that, with no clear picture of the problem, tailoring responses will prove difficult.

The need to gather evidence on drugs and driving, as a basis for effective responses in prevention and enforcement, is underlined in the latest edition of Drugs in focus, the EMCDDA’s policy briefing. In it, the agency summarises key issues now facing policymakers in this area and outlines innovative developments.

‘Reducing the loss of life caused by driving under the influence of psychoactive substances requires measures that are based on a scientific understanding of this complex phenomenon’, says EMCDDA Director Wolfgang Götz. ‘The challenge to legislators is to design sound and effective laws that can be enforced, and that give a clear message to the public’.

The release of the publication to policymakers is timely. At the start of the European road safety programme in 2003, it was estimated that over 40,000 people were dying on Europe’s roads every year. The programme set the ambitious target of halving the number of road deaths in Europe by the end of 2010. Next year the European Commission’s DRUID project (Driving under the influence of alcohol, drugs and medicines), which provides scientific support to this target, also comes to a close (2). DRUID aims to provide a solid basis for harmonised, EU-wide regulations for driving under the influence of alcohol, drugs and medicines.

Policy considerations presented in today’s briefing include:

- Surveys on the prevalence of drugs in drivers should be carried out in all EU Member States. At minimum, testing all drivers involved in a fatal accident for drugs and alcohol would provide an important source of information for monitoring the problem. Despite a European Commission recommendation in 2002 for such tests, few countries have adopted them and data remain scarce.

- Studies undertaken in this field need to be comparable if results are to be compiled. The EMCDDA and the European Commission have contributed to new international guidelines on study design that take into account differences between countries’ legislation and testing policies. These provide over 100 recommendations in the areas of behaviour, epidemiology and toxicology (3).

- Legal definitions of driving under the influence of drugs differ among EU Member States. Eleven countries have adopted a ‘zero tolerance’ approach penalising any driving after drug taking. Eleven others only penalise when there is evidence that driving performance has been impaired. Seven countries use a tiered response using both approaches. The level at which a driver will be deemed in breach of the law should be clear for all stakeholders and the public.

- Psychoactive medicines, whether consumed legally or not, can impair driving skills. National laws and their enforcement need to strike a balance between concerns about ensuring road safety and the therapeutic needs of individuals; to this end, some countries have adopted a two-tier penalty system. Providing clear information, such as a pictogram, on psychoactive medicines that affect driving ability may prevent patients from driving while adversely affected. But this is currently reported by only five countries.

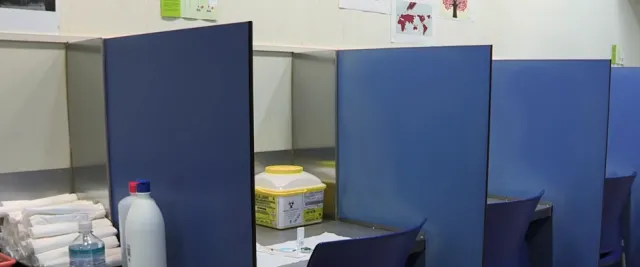

- As yet there is no agreement on a reliable on-site saliva-testing device. The EU’s Rosita-2 project could not recommend any of the nine devices evaluated between 2003 and 2005. In France, drivers are screened with saliva tests, but prosecution is based on a blood sample. For this reason, police experience considerable difficulty with the accurate and rapid identification of drug driving at the roadside. With no reliable testing device available, traffic police need more training in spotting signs of impairment due to drugs. Despite a call by the European Commission in 2002 for mandatory training for traffic police, by 2007 only four countries (Belgium, Portugal, Sweden, UK) reported obligatory training in this area.

- General messages that reach young cannabis users are unlikely to be listened to, or even noticed, by older users of psychoactive medicines and vice versa. Similarly, both groups may feel that warnings about alcohol do not apply to them. Thus, key audiences may not be hearing the message, or they may be ignoring it. Prevention efforts are more likely to succeed if they are tailored to specific substances and groups.

After alcohol, cannabis and benzodiazepines are the psychoactive substances most prevalent among Europe’s driving population. Studies on the impact of psychoactive substances on driving performance suggest that while both illicit and therapeutic drugs can affect driving, the effects can vary greatly from substance to substance.

Drugs in focus No 20 is available in 25 languages.

For a full range of EMCDDA products on drugs and driving, see the Drugs and driving thematic page.